- Joined

- Dec 3, 2020

- Messages

- 1,293

Every January, the world's top economists gather to discuss what matters most for the profession. And while it is easy to mistake the belligerent hostility of Nouriel Roubini (aka Dr. Doom) as symptomatic for the profession, the conference paints a rather different picture. In this article, I want to give an overview of how economists look at the blockchain — at least as seen through the lense of the 2019 AEA meetings.

Panel of Fed Chairpersons at the AEA 2019 meeting. Source.

The American Economic Association (AEA) organizes its annual meeting every year around this time for their flagship conference. Aside from top-level panel discussions and the faceless conference rooms (more or less) full of economists listening to the latest research, the conference is a focal point for the profession because most universities use it to recruit new faculty members. This year, the conference is in Atlanta and if you are interested in the full program, you can find it here. Presenting at the conference is prestigious, and only about 10–15% of papers are accepted for presentation.

How Economists see the Blockchain

For this article, I focus on paper sessions and leave out, for example, the panelon “Blockchain: Myth and Reality” or the various excellent poster sessions.

There were seven sessions more or less directly relevant to blockchain, which is a lot (but by no means puts blockchain on top of economists’ agenda this year). The seven sessions are:

UCT launched a course on Financial Regulation in Emerging Markets and the Rise of Fintech Companies. Check it out if you are interested in blockchain economics.The Economics of Initial Coin Offerings

Economists are fascinated with ICOs, not least because there is great data available on them. ICOs are interesting because for a while they have been killing VC funding. Since fintech startups have basically no tangible assets, and since banks tend to provide loans only against tangible collateral, startups are crucially dependent on VC funding. But the venture capital industry has its own special kind of frictions, and for years now startups have been complaining about the industry.

Lyandres and Chod (2018) develop a theory of ICOs and point to an important aspect of why entrepreneurs issuing ICOs “Selling tokens, which represent claims to the venture’s future revenue, allows an entrepreneur to transfer some of the venture risk to diversified investors without diluting her control rights.” Not diluting control rights sounds like a good thing, but as I have argued before, separating ownership and management is a fundamental lesson of incomplete contracts. Consequently, Lyandres and Chod show that “ICOs can dominate traditional venture capital (VC) financing when […] the degree of information asymmetry between the entrepreneur and ICO investors is not too large.” But that's exactly the crux. In almost all cases I can think of, there is a vast information asymmetry between entrepreneurs and ICO investors. This is why I think we should regulate ICOs and protect retail investors.

In their paper on Initial Coin Offerings and Platform Building, Li and Mann (2018) study another positive aspect of ICOs and argue that “By transparently distributing tokens before the platform operation begins, an ICO overcomes later coordination failures during platform operation, induced by a cross-side network effect between transaction counterparties.” So, effectively, Li and Mann argue that ICOs can act as a coordination mechanism to resolve strategic complementarities in two-sided networks. They also argue that ICOs resolve the issue of critical mass in user adoption, which is in line with the argument that ICOs can provide value by generating a signal about future demand for the platform.

Finally, Cong, Li, and Wang (2018) provide a dynamic model of cryptocurrencies and tokens that serve as means of payment among (blockchain-based) platform users. Complementarities in adoption are also at the heart of their model, and they argue that “Introducing tokens capitalizes future growth because the expected technological progress and popularity of the platform render tokens an attractive store of value, inducing further adoption.”

What I find surprising in this literature is the lack of studies of the negativeeffects of ICOs. In the same way that ICOs act as a coordination mechanism to resolve coordination issues, they also introduce strategic complementarities among investors, just in the same way costly liquidation does in the classic Diamond and Dybvig (1983) model does among depositors. I would be very curious to see a paper studying these negative externalities in more detail, because it can help us understand how the crypto bubble burst in early 2018 (Cong and He provide some clues in their forthcoming RFS paper on smart contracts, arguing that smart contracts can enable collusion).

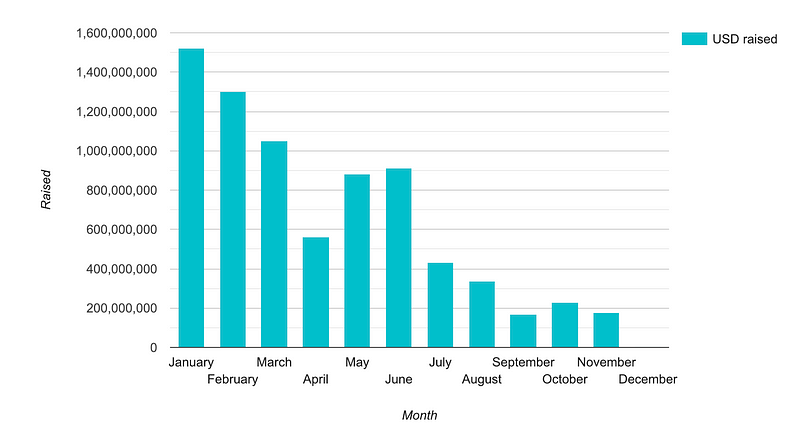

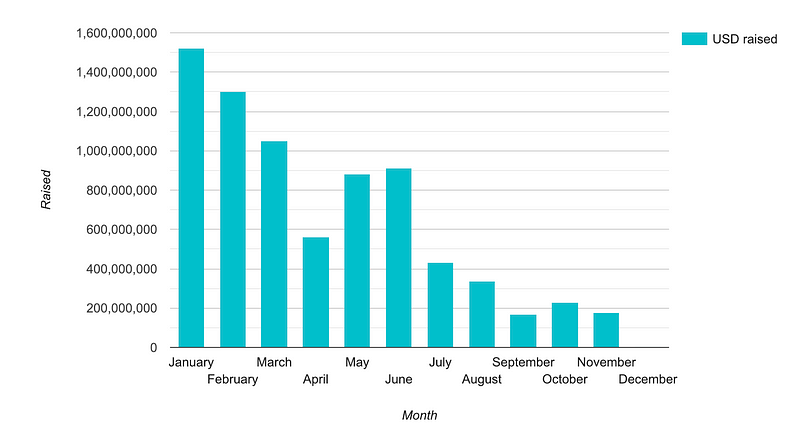

The ICO market is collapsing. Source.Blockchain Economics

A number of papers study the economics of the blockchain itself, most commonly the incentives to adopt a blockchain. This is the economist's version of the famous "Do I need a blockchain?" flowchart.

Biais, Bisiere, Bouvard, and Casamatta have written a short but extremely timely paper on forks (just think of the BCH fork insanity). Cryptocurrency proponents often argue that the total supply of coins is fixed and that this algorithmic commitment can keep inflation better in check than untrustworthy central banks (sic) can do. Leaving aside that the maximalists ignore some very basic lessons of optimal currency areas already highlightedby Mundell in 1961, they also ignore the risk of forks that are the crypto-world equivalent of inflation (just with more drama and better live streams).

Biais et al argue that “The blockchain protocol […] is a coordination game, with multiple equilibria. There exist equilibria with forks, leading to orphaned blocks and persistent divergence between chains.” and show how forks can be generated by information delays and software upgrades. They also point to a big problem in the crypto mining industry: excessive capacity: “We identify negative externalities implying that equilibrium investment in computing capacity is excessive.”

In their paper, Abadi and Brunnermeier study the question when intermediaries are not sufficient safeguards to protect the integrity of ledgers. They argue that “Blockchains/DLT also rely on miners’ competition as miners’ free entry rules out any dynamic incentivization via franchise value, the core mechanism the traditional centralized intermediary arrangement relies on.” They also highlight a key shortcoming of blockchains, the enforcement of digital blockchain records in the physical world, writing that “While blockchains can keep track of transfer of ownership, proper enforcement of possession rights is still needed, except in the case of (fiat) cryptocurrencies.”

Bitcoin and the economics of decentralization

The third big block of papers studies the economic incentives of bitcoin and the quest for decentralization.

Huberman, Leshno, and Moallemi (2018) conduct "An Economic Analysis of the Bitcoin Payment System". They derive closed form formulas of the fees and waiting times in Bitcoin and study their properties; compare the economics of the Bitcoin payment system (BPS) to that of a traditional payment system operated by a profit maximizing firm; and suggest protocol design modification to enhance the platform’s efficiency. It is far from clear why Bitcoin — or any cryptocurrency for that matter — are a superior payment system. The only real argument I have seen so far is that people do not trust central banks (who most commonly operate national payment systems) or that international payments are ridiculously expensive, courtesy of Visa, Mastercard, and SWIFT. But for the purpose of domestic payments, it is hard to make a case for Bitcoin over e.g. fed funds, TARGET2, or CHAPS. Understanding Bitcoin as a payment system therefore helps us to understand when it is a viable alternative, and when it is not.

In his paper, Pagnotta (2018) asks questions along a similar line and “characterize how the network technologies and participants, users and miners, affect the number and dynamic stability properties of equilibria.” While many crypto proponents claim not to care about the price, the success of the industry critically hinges on the market price because many startups will not have converted the funding they raised in ICOs into fiat (Vinny Lingham has some enlightened thoughts on this topic in his twitter feed). In fact, I think one of the key drivers of market prices at the moment are the strategic complementarities between entrepreneurs who still have substantial crypto holdings as they struggle to convert them into fiat.

Leaving this aside, Pagnotta continues “We find that the relation between bitcoin prices and the supply growth rate is not monotonic: the same price is consistent with different rates. The model’s outcomes demonstrate how intrinsic price–security feedback effects can amplify or moderate the price volatility effect of demand shocks.” Importantly, Pagnotta finds that “rational patterns of price momentum and crashes, and that small and large stochastic bubbles can exist in general equilibrium and show how the probability of bursting decreases with the bitcoin price.”

We are only at the beginning in understanding the price dynamics in the crypto asset markets. But these price dynamics matter, not only for the duped retail investor who lost it all during the bubble, but also for entrepreneurs and ultimately for regulators. The last set of papers goes even further and studies these markets empirically. Given the wide availability of data, I believe we will see many post-mortem analyses of these markets in the near future.

What drives prices in crypto asset markets?

A number of papers study Initial Coin Offerings empirically, often using impressive datasets. Others study the market for crypto assets using tools from asset pricing theory. This is an important contribution because these markets are rife with anomalies and understanding them will go a long way in normalizing crypto assets as an investment vehicle. As long as there is no level playing field in crypto asset markets, it is unlikely that regulators like the SEC will look favorably on them. This research is good news for anyone (still) holding crypto, because it can help weed out unsavory actors, as the researchby John M. Griffin and Amin Shams on “Is Bitcoin Really Un-Tethered?” shows.

Presenting at the AEA, Hu, Parlour, and Rajan (2018) find that “secondary market returns of all other currencies are strongly correlated with Bitcoin returns”, which is not surprising to anyone watching crypto markets where every day is either red or green. What is much less clear at this point — and none of the papers at the AEA really go into this — is why markets are so highly correlated.

Howell, Niessner, and Yermack (2018) conclude in their impressive study of 453 ICOs that “[…] liquidity and trading volume are higher when issuers offer voluntary disclosure, credibly commit to the project, and signal quality.” This is an important point, but not something that will surprise anyone active in the crypto investment space. What makes this paper different from the many industry and community approaches is the rigor of the study. Aside from anecdotes whispered in hushed voices, now we have some reliable numbers. The only downside here is that the market for ICOs is largely over, so that this is more of a post-mortem analysis.

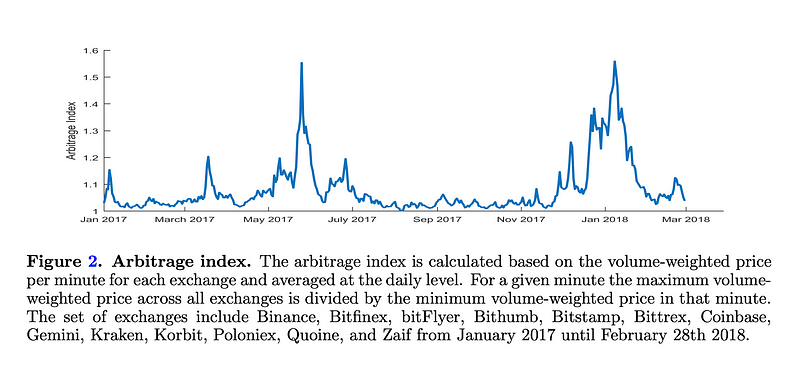

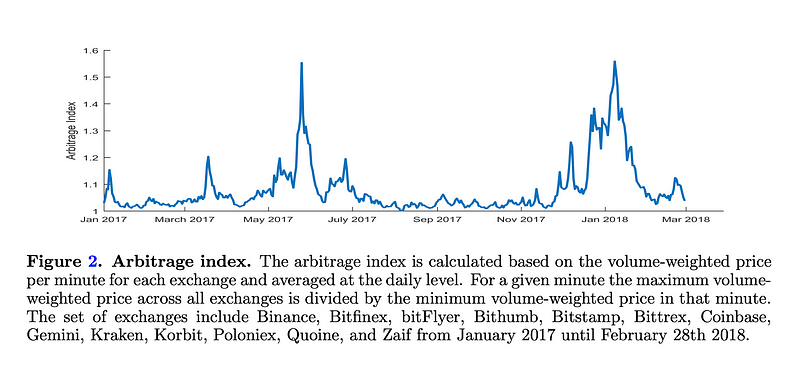

The arbitrage index shown in Schoar and Makarov (2018). Source.

Finally, Schoar and Makarov (2018) document “large, recurrent arbitrage opportunities in cryptocurrency prices relative to fiat currencies across exchanges, which often persist for weeks.” and then “Price deviations are much larger across than within countries, and smaller between cryptocurrencies.”Again, this is a phenomenon you could read a lot about in telegram or discord channels, but it is important to document the arbitrage opportunities in crypto markets rigorously and study where they come from. The conclusion in the paper is that capital controls are the likely friction behind the persistent arbitrage opportunity, which is interesting because it tells us something about the use of crypto assets to avoid existing regulations.

Conclusion

It is amazing to see how much economists can enhance our understanding of crypto markets. Sure, crypto maximalists will not always like what they read and disregard some of this work as “fiat economics”, but in the longer run, economic fundamentals always win the day. Let's see if next year's AEA in San Diego will have a similarly strong showing of blockchain research, or if the hype will be largely over by then.

Panel of Fed Chairpersons at the AEA 2019 meeting. Source.

The American Economic Association (AEA) organizes its annual meeting every year around this time for their flagship conference. Aside from top-level panel discussions and the faceless conference rooms (more or less) full of economists listening to the latest research, the conference is a focal point for the profession because most universities use it to recruit new faculty members. This year, the conference is in Atlanta and if you are interested in the full program, you can find it here. Presenting at the conference is prestigious, and only about 10–15% of papers are accepted for presentation.

How Economists see the Blockchain

For this article, I focus on paper sessions and leave out, for example, the panelon “Blockchain: Myth and Reality” or the various excellent poster sessions.

There were seven sessions more or less directly relevant to blockchain, which is a lot (but by no means puts blockchain on top of economists’ agenda this year). The seven sessions are:

- Technological Change and Social Provisioning

- Blockchain Economy and Cryptocurrency Markets

- Blockchain and Tokenomics

- Blockchain and Cryptocurrencies

- Economics of Financial Technology

- The Digital Agenda of Virtual Currencies in the Bitcoin Age: Regulation, Anonymity and Cybercrime

- Crypto-currency Markets

UCT launched a course on Financial Regulation in Emerging Markets and the Rise of Fintech Companies. Check it out if you are interested in blockchain economics.The Economics of Initial Coin Offerings

Economists are fascinated with ICOs, not least because there is great data available on them. ICOs are interesting because for a while they have been killing VC funding. Since fintech startups have basically no tangible assets, and since banks tend to provide loans only against tangible collateral, startups are crucially dependent on VC funding. But the venture capital industry has its own special kind of frictions, and for years now startups have been complaining about the industry.

Lyandres and Chod (2018) develop a theory of ICOs and point to an important aspect of why entrepreneurs issuing ICOs “Selling tokens, which represent claims to the venture’s future revenue, allows an entrepreneur to transfer some of the venture risk to diversified investors without diluting her control rights.” Not diluting control rights sounds like a good thing, but as I have argued before, separating ownership and management is a fundamental lesson of incomplete contracts. Consequently, Lyandres and Chod show that “ICOs can dominate traditional venture capital (VC) financing when […] the degree of information asymmetry between the entrepreneur and ICO investors is not too large.” But that's exactly the crux. In almost all cases I can think of, there is a vast information asymmetry between entrepreneurs and ICO investors. This is why I think we should regulate ICOs and protect retail investors.

In their paper on Initial Coin Offerings and Platform Building, Li and Mann (2018) study another positive aspect of ICOs and argue that “By transparently distributing tokens before the platform operation begins, an ICO overcomes later coordination failures during platform operation, induced by a cross-side network effect between transaction counterparties.” So, effectively, Li and Mann argue that ICOs can act as a coordination mechanism to resolve strategic complementarities in two-sided networks. They also argue that ICOs resolve the issue of critical mass in user adoption, which is in line with the argument that ICOs can provide value by generating a signal about future demand for the platform.

Finally, Cong, Li, and Wang (2018) provide a dynamic model of cryptocurrencies and tokens that serve as means of payment among (blockchain-based) platform users. Complementarities in adoption are also at the heart of their model, and they argue that “Introducing tokens capitalizes future growth because the expected technological progress and popularity of the platform render tokens an attractive store of value, inducing further adoption.”

What I find surprising in this literature is the lack of studies of the negativeeffects of ICOs. In the same way that ICOs act as a coordination mechanism to resolve coordination issues, they also introduce strategic complementarities among investors, just in the same way costly liquidation does in the classic Diamond and Dybvig (1983) model does among depositors. I would be very curious to see a paper studying these negative externalities in more detail, because it can help us understand how the crypto bubble burst in early 2018 (Cong and He provide some clues in their forthcoming RFS paper on smart contracts, arguing that smart contracts can enable collusion).

The ICO market is collapsing. Source.Blockchain Economics

A number of papers study the economics of the blockchain itself, most commonly the incentives to adopt a blockchain. This is the economist's version of the famous "Do I need a blockchain?" flowchart.

Biais, Bisiere, Bouvard, and Casamatta have written a short but extremely timely paper on forks (just think of the BCH fork insanity). Cryptocurrency proponents often argue that the total supply of coins is fixed and that this algorithmic commitment can keep inflation better in check than untrustworthy central banks (sic) can do. Leaving aside that the maximalists ignore some very basic lessons of optimal currency areas already highlightedby Mundell in 1961, they also ignore the risk of forks that are the crypto-world equivalent of inflation (just with more drama and better live streams).

Biais et al argue that “The blockchain protocol […] is a coordination game, with multiple equilibria. There exist equilibria with forks, leading to orphaned blocks and persistent divergence between chains.” and show how forks can be generated by information delays and software upgrades. They also point to a big problem in the crypto mining industry: excessive capacity: “We identify negative externalities implying that equilibrium investment in computing capacity is excessive.”

In their paper, Abadi and Brunnermeier study the question when intermediaries are not sufficient safeguards to protect the integrity of ledgers. They argue that “Blockchains/DLT also rely on miners’ competition as miners’ free entry rules out any dynamic incentivization via franchise value, the core mechanism the traditional centralized intermediary arrangement relies on.” They also highlight a key shortcoming of blockchains, the enforcement of digital blockchain records in the physical world, writing that “While blockchains can keep track of transfer of ownership, proper enforcement of possession rights is still needed, except in the case of (fiat) cryptocurrencies.”

Bitcoin and the economics of decentralization

The third big block of papers studies the economic incentives of bitcoin and the quest for decentralization.

Huberman, Leshno, and Moallemi (2018) conduct "An Economic Analysis of the Bitcoin Payment System". They derive closed form formulas of the fees and waiting times in Bitcoin and study their properties; compare the economics of the Bitcoin payment system (BPS) to that of a traditional payment system operated by a profit maximizing firm; and suggest protocol design modification to enhance the platform’s efficiency. It is far from clear why Bitcoin — or any cryptocurrency for that matter — are a superior payment system. The only real argument I have seen so far is that people do not trust central banks (who most commonly operate national payment systems) or that international payments are ridiculously expensive, courtesy of Visa, Mastercard, and SWIFT. But for the purpose of domestic payments, it is hard to make a case for Bitcoin over e.g. fed funds, TARGET2, or CHAPS. Understanding Bitcoin as a payment system therefore helps us to understand when it is a viable alternative, and when it is not.

In his paper, Pagnotta (2018) asks questions along a similar line and “characterize how the network technologies and participants, users and miners, affect the number and dynamic stability properties of equilibria.” While many crypto proponents claim not to care about the price, the success of the industry critically hinges on the market price because many startups will not have converted the funding they raised in ICOs into fiat (Vinny Lingham has some enlightened thoughts on this topic in his twitter feed). In fact, I think one of the key drivers of market prices at the moment are the strategic complementarities between entrepreneurs who still have substantial crypto holdings as they struggle to convert them into fiat.

Leaving this aside, Pagnotta continues “We find that the relation between bitcoin prices and the supply growth rate is not monotonic: the same price is consistent with different rates. The model’s outcomes demonstrate how intrinsic price–security feedback effects can amplify or moderate the price volatility effect of demand shocks.” Importantly, Pagnotta finds that “rational patterns of price momentum and crashes, and that small and large stochastic bubbles can exist in general equilibrium and show how the probability of bursting decreases with the bitcoin price.”

We are only at the beginning in understanding the price dynamics in the crypto asset markets. But these price dynamics matter, not only for the duped retail investor who lost it all during the bubble, but also for entrepreneurs and ultimately for regulators. The last set of papers goes even further and studies these markets empirically. Given the wide availability of data, I believe we will see many post-mortem analyses of these markets in the near future.

What drives prices in crypto asset markets?

A number of papers study Initial Coin Offerings empirically, often using impressive datasets. Others study the market for crypto assets using tools from asset pricing theory. This is an important contribution because these markets are rife with anomalies and understanding them will go a long way in normalizing crypto assets as an investment vehicle. As long as there is no level playing field in crypto asset markets, it is unlikely that regulators like the SEC will look favorably on them. This research is good news for anyone (still) holding crypto, because it can help weed out unsavory actors, as the researchby John M. Griffin and Amin Shams on “Is Bitcoin Really Un-Tethered?” shows.

Presenting at the AEA, Hu, Parlour, and Rajan (2018) find that “secondary market returns of all other currencies are strongly correlated with Bitcoin returns”, which is not surprising to anyone watching crypto markets where every day is either red or green. What is much less clear at this point — and none of the papers at the AEA really go into this — is why markets are so highly correlated.

Howell, Niessner, and Yermack (2018) conclude in their impressive study of 453 ICOs that “[…] liquidity and trading volume are higher when issuers offer voluntary disclosure, credibly commit to the project, and signal quality.” This is an important point, but not something that will surprise anyone active in the crypto investment space. What makes this paper different from the many industry and community approaches is the rigor of the study. Aside from anecdotes whispered in hushed voices, now we have some reliable numbers. The only downside here is that the market for ICOs is largely over, so that this is more of a post-mortem analysis.

The arbitrage index shown in Schoar and Makarov (2018). Source.

Finally, Schoar and Makarov (2018) document “large, recurrent arbitrage opportunities in cryptocurrency prices relative to fiat currencies across exchanges, which often persist for weeks.” and then “Price deviations are much larger across than within countries, and smaller between cryptocurrencies.”Again, this is a phenomenon you could read a lot about in telegram or discord channels, but it is important to document the arbitrage opportunities in crypto markets rigorously and study where they come from. The conclusion in the paper is that capital controls are the likely friction behind the persistent arbitrage opportunity, which is interesting because it tells us something about the use of crypto assets to avoid existing regulations.

Conclusion

It is amazing to see how much economists can enhance our understanding of crypto markets. Sure, crypto maximalists will not always like what they read and disregard some of this work as “fiat economics”, but in the longer run, economic fundamentals always win the day. Let's see if next year's AEA in San Diego will have a similarly strong showing of blockchain research, or if the hype will be largely over by then.